Every well informed freshwater ichthyologist is familiar with petfrd.com forum. Petfrd does not easily translate to Singapore Cichlid Community, which seems to be the patron of the site, but I have no clue to what petfrd could mean. The forum has several sections, and postings are enthusiastic and often with beautiful images of habitats or fresh collected fish contributed by local aquarists from all over southern Asia (and others, sure) . Ng Heok Hee moderates a section about scientific literature and usually is abreast of locating new papers about cichlids or Asian fishes. So, here is the secret about staying informed: daily visits to petfrd.com!

In January 2008, information and photos were posted of what looked like a danio but sufficiently different not to be ignored as ‘one more…’. ‘Beta’, with a sad smiley reported that his fish were in the freezer. Fang immediately got in contact with ‘Beta’, whose name is actually Beta Mahatvaraj, enthusiastic Indian aquarist. His five frozen fish were preserved in ethanol and formalin and shipped to us. They weren’t really fresh, and the colour somewhat faded, but still all anatomy and DNA could be extracted from hem. Fang started writing up a description and gave it a manuscript name, ‘Betadevario longibarbis’.

It wasn’t a Danio as some of the first reports had it. It was more like a Devario, with those longitudinal depressions above each eye filled with sensory organs, characterizing Devario and Chela. But still not looking like a Devario, above all because of the long barbels, but also with regard to the coloration, which is unique among danios, with a light band along the middle of the side, and dark abdominal sides. Devario typically have very short barbels or they are missing completely, whereas most Danio have long barbels.

Actually, Devario is a speciose genus with more than 50 species, many still undescribed, and there is considerable variation in shape and colour pattern among them. They never have long barbels, though.

Since everything takes long time for us (the Cichla revision published 2006 took 17 years, and other papers not published were written in the 1980s, to give you a hint), it wasn’t unexpected to learn in 2009 that an Indian team was also working with the same species, and also with very few specimens. It took till December 2009 before we established contact and things were arranged for a collaborative effort to get the fish described. In the meantime much more material had become available, and indeed there were already numerous presentations of the fish on the web, e.g., in PFK and in several Indian news sites. Collaborating meant we could provide a fairly complete review of the new species with habitat data and image, live colour photo, and molecular and morphological phylogenetic analysis, better than individual papers would have been. Betadevario got the species epithet ramachandrani for A. Ramachandran. Our molecular and morphological analyses differ with regard to its placement in the phylogenetic tree, but it is certainly a very basal taxon among Devario like danios, and we have more confidence in the molecular data which places it as sister group to other Devario.

Why not make it a Devario then? A good question for any genus, and will never have a good answer for all who come up with it. In this case we reasoned that the molecular analysis provided better clarity. The morphological dataset was good for distinguishing Devario and Danio, but not for resolving relationships within Devario. We have to work a lot more on that. And we are doing it, with both morphology and molecules. Betadevario presents a unique colour pattern and long barbels to distinguish it from all Devario (including Inlecypris), providing a morphological justification for the genus.

The largest specimens measured about 60 mm. There are no characters to distinguish males and females, except the tubercles on the pectoral fin in males, a secondary sex indicator shared with most Danio and Devario. Information on live colours are not in concert. The live fish on Beta Mahatvaraj’s image are golden and brown/blackish, whereas the illustration by P.K. Pramod shows a a fish with a blue stripe along the side and lemon yellow fins. It will be interesting to see Betadevario alive sometime. It does not look like it will be a big aquarium fish, but who can say. It is so far known only from a small mountain stream in the Western Ghats, with relatively cool water, and may be expected to be sensitive to transportation.

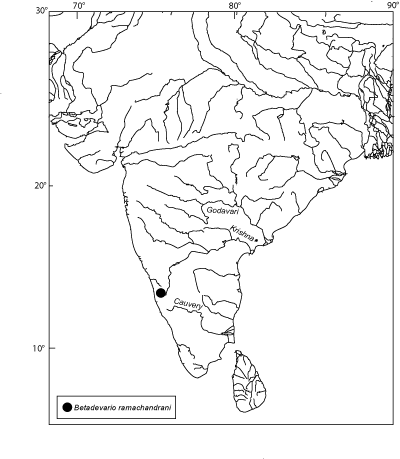

Betadevario ramachandrani is known only from a very small area in the Western Ghats, the mountain range along the western coast of India, where it lives in fast running clear waters in the forest.

You don’t need a longer story here. The full description of Betadevario ramachandrani with habitat image, trees, and other details is available free to download from the Zootaxa website.

Reference

Pramod, P.K., F. Fang, K. Rema Devi, T.-Y. Liao, T.J. Indra, K.S. Jameela Beevi & S. O. Kullander. 2010. Betadevario ramachandrani, a new danionine genus and species from the Western Ghats of India (Teleostei: Cyprinidae: Danioninae). Zootaxa, 2519: 31-47.

Credits

Thanks to Beta Mahatvaraj and P.K. Pramod for making the images of live fish available.