The latest issue of the annual proceedings of the Swedish Linnaean Society (Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift, 2010) has an interesting article by Gudrun Nyberg bearing the title Ögontröst En biografi över naturforskaren Bengt Andersson Euphrasén 1755-1796. ( Eyebright A biography of the natural scientist Bengt Andersson Euphrasén 1775-1796. ) Euphrasén is (and was) one of the lesser known Swedish ichthyologists (although I bet most readers will be at a loss to call to mind any number of Swedish ichthyologist at all …). He did not live to see anything significant ichthyological really accomplished, and his biography is verdict of that. Indeed he may be best known for his book about St. Barthélemy, mainly on plants. That would take us to a different story, though.

Euphrasén was born apparently 26 April 1755, son to a farmer in Myrebo (could translate to “Antnest” as well as “Bognest”) in the western part of Sweden. Himself he seems to have lived in the illusion that he was born sometime in April 1756. He was baptized Bengt Andersson. Somehow he was given a good education, attending boarding school on Visingsö Island from 1772 as Benedictus Arén Haboënsis. For a while he attended a veterinary curriculum in Skara with the taken name Euphrasén, from the plant Euphrasia stricta (or some other species of Euphrasia). This is the only case I know of where someone has borrowed a scientific name for last name. It is always the other way. Perhaps an easy way of getting oneself a patronym? He returned to and graduated from high school in 1780, immediately signing on as sailor on a ship to China. Already in school he had become addicted to Botany and now on the trip to and from China he observed and collected fish. Very few of them it seems, five were described as new. Euphrasén wasn’t going to litter ichthyological nominospace.

Back home in 1783 he sold or handed over his catch to a wealthy merchant, Clas Alströmer in Gothenburg, who had a natural history cabinet. From now on Alströmer and Euphrasén interacted in various ways. Alströmer employed Euphrasén to curate his collections and eventually, when his finances fell low, move them to Gåsevadholm Castle in Halland. In 1787 Alströmer obtained support from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for a trip to the Swedish West Indies, the island of St. Barthélemy, where Euphrasén made collections, mostly plants. Upon his return Euphrasén marrried to Maria Greta Hallberg and they had a son in 1793, but it seems Euphrasén left Gothenburg and his family for good in the spring of 1794, after the passing of Alströmer. He moved to Stockholm where he worked in the Academy as some kind of assistant to Anders Sparrman. His manuscript about St. Barthélemy was somehow turned down by the Academy in 1792 following Sparrman’s review, but eventually it came out with Academy support in 1795. Interesting about this St. Barts thing relates to the fish. He had bought two specimens of a strange kind of cod in the harbour of Gothenburg in 1787 but they deteriorated on the way to St. Barts and were discarded. Imagine: collects a new species in Sweden and takes the specimens along to St. Barts, just to lose them to putrefaction, … well, well. Upon return it took some time to find a new one, and only in 1793 one came into his hands. He described it as Gadus lubb, and quite in vain as it is a synonym of Brosme brosme (Ascanius, 1772).

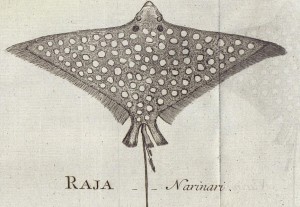

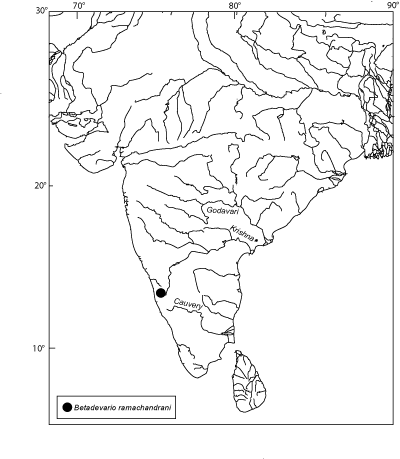

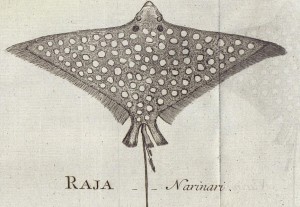

Raja narinari = Aetobatis narinari, described from the Swedish West Indies. Drawing from Euphrasén, 1790, tail not shown.

At some point Euphrasén got himself working on a manuscript about Bohuslän’s fishes. As we all know, that’s all the Swedish marine fauna, and what is beyond that is not much, so at some later point he decided on and completed a Swedish Ichthyology, covering all Swedish fish species. In the late 1700s a national ichthyology was quite something innovative. The Academy, however, apparently refused to print it. The manuscript, describing 106 species of fishes, is preserved in the library of Lund University. Euphrasén died in December 1796, of hernia. Poor, misunderstood, in conflict with colleagues, writer of masterpieces. There is no portrait.

There is of course a lot more to this biography, for which Gudrun Nyberg’s illustrated article better be consulted. Aside from calling attention to an earlier, relatively unnoticed colleague of mine (the Academy’s natural history collection became the Swedish Museum of Natural History where I work as a curator), I just wish to expose here some aspects of ichthyological concern.

Plants from the St. Barthélemy expedition were bought by Carl Peter Thunberg for the Uppsala University (Wikström 1825), displaying 113 objects online. Others are still in existence in the Botany department of the Swedish Museum of Natural History. They have 106 online items with Euphrasén as collector. Unfortunately, the fishes seem to be gone altogether. The Swedish Museum of Natural History has specimens from one or more of the many Alströmer and the Academy, but nothing definitely from Euphrasén. Jonas Alströmer, father of Clas, was also a collector of natural history objects, and some part of his collection has found its way at least to the Museum of Evolution in Uppsala, but it still remains to be investigated what happened to the collections of Clas, and those of Euphrasén. The type of Gadus lubb was deposited in the Swedish Museum of Natural History, but apparently is no longer present there.

Interestingly, all of Euphrasén’s fish works are available online in one or another form. The St. Barthélemy treatise is published online by the Biodiversity Heritage Library. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences are publishing their Transactions online, and they include the four fish papers by Euphrasén. Well, they are all in Swedish, an older form which is not covered by Google Translate, but at least you can admire the elegant woodcuts. Obviously not much was needed those days to get a fish description done. The mystery remains, however: How come Euphrasén, travelling to the two extremes of the world, Asia and America, with all the world’s unknown tropical fish fauna within reach, obviously didn’t make more discoveries? He even failed with two out of three Swedish species, Gadus lubb (Bromse brosme ) and Gobius ruuthensparri (=Gobiusculus flavescens). Why wasn’t his Swedish Ichthyology published? What makes people become ichthyologists?

The first publication, Trangrums-Acten (” The fish oil sediment document”), from 1784 happens to be an environmental impact assessment study, maybe the first scientific of its kind in Sweden. At the time, herring was abundant and the production of fish oil boomed along the northern part of the Swedish West Coast. The oil was produced by fermentation and boiling in many hundreds of seaside factories. It was used for just about everything and it made Clas Alströmer and others rich. Regrettably, there was considerable waste of herring liberated from their oil. (The firs major oil sanitation operation in the world?) Waste products were dumped in the sea next to each factory, apparently producing local deoxygenation in addition to enrichening the air with the smell of millions and millions of rotten herring. The Stockholm based central government introduced a number of restrictions to reduce expected habitat detoriation (and curtail the increased wealth and political influence of the west coast companies?). That upset the oil companies, who responded with arguments in Trangrums-Acten. It resulted in the compromise solution to construct shorenear ponds to contain the smelly offal. Clas Alströmer was active in the investigations, but most of the work seems to have resulted from the coordination by Johan Lorenz Rutensparre (1752-1828), actually a naval military, but one of Sweden’s first environmental economists in his spare time. At a field excursion in 1783, Euphrasén obviously found specimens of a new species, of which Gobius ruuthensparri was described first in Trangrums-Acten, , but without name.

Bengt Andersson Euphrasén’s bibliography

Note on online content: Most of he Academy Transaction papers are provided by the Royal Academy of Sciences Center for the History of Science. The German translations of Academy Transactions are provided by the University of Göttingen only up to 1788.

Euphrasén published as Bengt And. Euphrasén; where And. is short for Andersson, his original last name, but it is usually believed to be a first name (Anders). Indeed, in the 1786 paper his name is printed Bengt Anders Euphrasén, but that could be an editorial or printer’s decision. At the time children would automatically have the last name formed from the first name of their father (Euphrasén’s father was named Anders), but to this could be added something more distinctive, so that a double last name was common, as in today’s Latin America, Spain and Portugal. Not to complicate matters further, he is cited as Euphrasén, B.A. below, as people usually do. [It should be Andersson Euphrasén, B.]

Ruuthensparre, J.L., J. Kiermanskiöld & A. Dahl. 1784. Utdrag af den Dagbok, som hölts under en Undersöknings Förrättning i Bohus Länska Skärgården åren 1783 och 1784. Pp. 18-65 In Anonymous. Trangrums-acten, eller Samling af de handlingar, som med kongl. maj:ts allernådigste tilstånd blifwit des och rikets höglofl. amiralitets- och commerce-collegier tilsände, rörande tran-beredning af sill, uti Bohus länska skärgården, : och bewis derpå, at det uti hafswattnet utkastade trangrums skadar hwarken hamnar, farleder eller fiske, hwilket man tilförene befarat. I anseende til ämnets wigt, almän uplysning och beqwämare bruk, til tryck befordrad af några götheborgare, : som anlagt transiuderier uti Bohus länska skärgården. Stockholm, tryckt i kongl. tryckeriet. [Apparently the fish identifications and notes are by Euphrasén, but he is not mentioned. A new species of Gobius is mentioned on p. 52, but it it is named only in the 1786 paper, as Gobius ruuthensparri .]

Euphrasén, B.A. 1786. Beskrifning på tvenne Svenska Fiskar. Kongl. Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar, 7: 64-67.

Gobius Ruuthensparri = Gobiusculus flavescens (Fabricius 1779)

Cottus Bubalis = Taurulus bubalis (Euphrasén, 1786)

Euphrasén, B.A. 1788. Beskrifning på 3:e fiskar. Kongl. Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar, 9: 51-55.

Trichiurus Caudatus = Lepidopus caudatus (Euphrasén, 1788)

Stromateus argenteus = Pampus argenteus (Euphrasén, 1788)

Stromateus Chinensis = Pampus chinensis (Euphrasén, 1788)

Euphrasén, B.A. 1790. Raja (Narinari). Kongl. Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar, 11:217-219.

Raja Narinari = Aetobatus narinari (Euphrasén, 1790)

Euphrasén, B.A. 1791. Scomber (Atun) och Echeneis (Tropica). Kongl. Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar, 12:315-318.

Scomber Atun = Thyrsites atun (Euphrasén, 1791)

Echeneis tropica = Phtheirichthys lineatus (Menzies, 1791)

Euphrasén, B.A. 1794. Gadus Lubb, en ny Svensk fisk beskrifven. Kongl. Vetenskaps Academiens Nya Handlingar, 15: 223-227.

Gadus Lubb = Brosme brosme (Ascanius, 1772).

Euphrasén, B.A. 1795. Beskrifning öfver svenska westindiska ön St. Barthelemi, samt öarne St. Eustache och St. Christopher. Anders Zetterberg, Stockholm, vi + 207 pp.

Perca Holocentrus = Holocentrus adscensionis (Osbeck 1765)

German translations:

Euphrasén, B.A. 1787. Beschreibung von zwey schwedischen Fischen. Der Königlich Schwedischen Akademie der Wissenschaften neue Abhandlungen aus der Naturlehre, Haushaltungskunst und Mechanik. N. S., 7: 62-65.

Euphrasén, B.A. 1788. Beschreibung dreyer Fische. Der Königlich Schwedischen Akademie der Wissenschaften neue Abhandlungen aus der Naturlehre, Haushaltungskunst und Mechanik. N. S., 9: 47-51.

Euphrasén, B. A. 1792. Raja narinari. Der Königlich Schwedischen Akademie der Wissenschaften neue Abhandlungen aus der Naturlehre, Haushaltungskunst und Mechanik. Der Königlich Schwedischen Akademie der Wissenschaften neue Abhandlungen aus der Naturlehre, Haushaltungskunst und Mechanik. N. S., 11: 205-207.

Euphrasén, B.A. 1798. Herrn Bengt And. Euphraséns Reise nach der schwedisch-westindischen Insel St. Barthelemi, und den Inseln St. Eustache und St. Christoph; oder Beschreibung der Sitten, Lebensart der Einwohner, Lage, Beshaffenheit und natürlichen Produkte dieser Inseln. Aus dem Schwedischen von Joh. Georg Lud. Blumhof. Göttingen.

Non-fish:

Euphrasén, B.A. 1793. Historiskt frögde-qwäde, wid jubel-dagens firande d. 8 martii 1793; af B.A. Euphrasén. Götheborg, tryckt hos Lars Wahlström, 16 pp.

Linné, C. 1792. Archiatern och riddaren Carl von Linnees Termini botanici eller Botaniska ord, samlade och med anmärkningar på swenska öfwersatta af Bengt And. Euphrasén. Götheborg, tryckt hos Lars Wahlström, 76 pp.

Sources

Biographic data were condensed mostly from:

Nyberg, G. 2011. Ögontröst En biografi över naturforskaren Bengt Andersson Euphrasén 1755-1796. Svenska Linnésällskapets Årsskrift, 2010: 69-89.

Thanks to Erik Åhlander for information about possible Euphrasén collections in the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Bodil Kajrup, and the University Library in Gothenburg for assistance with publications. Synonymies were checked against the Catalog of Fishes.

On the night of 27 September 1735 suddenly ended the life of one of the most significant founders of the science of systematic biology when Petrus Artedi, Angermannius, drowned in a canal in Amsterdam. At the age of 30, he was still not a man of fame, and did not leave wife, children or portrait. Only manuscripts, the ichthyological ones edited and published by Carl Linnaeus in 1738.

On the night of 27 September 1735 suddenly ended the life of one of the most significant founders of the science of systematic biology when Petrus Artedi, Angermannius, drowned in a canal in Amsterdam. At the age of 30, he was still not a man of fame, and did not leave wife, children or portrait. Only manuscripts, the ichthyological ones edited and published by Carl Linnaeus in 1738. Artedi in love? In another novel, Peter Artedi Helenas son (Peter Artedi, Helena’s son), by Gun Frostling (202 pp., Nomen förlag, Visby, 2010), Artedi on the run after an embarrassing experience with his father, takes in at a countryside inn. Suddenly he whispers to the innkeeper’s daughter Katarina Ersdotter, “We have to be careful, miss Katarina” … The Katarina to whom he gives his final thoughts. Gun Frostling’s story is woven from the same fragmentary matter as all other Artedi biographies, but gives him a real life on top of all the academic stuff, a real home, real parents, a loving girl, and spoken lines. And who is Gun Frostling? An author off the grid?

Artedi in love? In another novel, Peter Artedi Helenas son (Peter Artedi, Helena’s son), by Gun Frostling (202 pp., Nomen förlag, Visby, 2010), Artedi on the run after an embarrassing experience with his father, takes in at a countryside inn. Suddenly he whispers to the innkeeper’s daughter Katarina Ersdotter, “We have to be careful, miss Katarina” … The Katarina to whom he gives his final thoughts. Gun Frostling’s story is woven from the same fragmentary matter as all other Artedi biographies, but gives him a real life on top of all the academic stuff, a real home, real parents, a loving girl, and spoken lines. And who is Gun Frostling? An author off the grid?