Although actinopterygian radiation seems to have made the most significant footprint in vertebrate diversity, with more than 30 000 Recent species, there are also scientists who looking into the origin of the less successful group, the sarcopterygians, among which the tetrapods are the terrestrial ones – except that some escaped back to the water (sirenians, seals, cetaceans, and the like).

Attending Catherine Boisvert’s defence of her dissertation The origin of tetrapod limbs and girdles: fossil and developmental evidence recently, I came to realize that the evolutionary quirk with tetrapods is not the possession of limbs – lots of actinopterygians have limbs, and many tetrapods lack them – but the presence of fingers. Catherine’s thesis is about the evolution of fingers and the pelvic girdle. The digits (fingers) sit at the end of the autopod (the hand and foot of tetrapods) and are homologous with the distal radials of the dermatotrichs (fin-rays) attached to fish proximal radials (the pectoral-fin base, homologous with the sarcopterygian/tetrapod limbs). Interestingly, the finrays and the digits form before the autopod and proximal radials in both sarcopterygians and actinopterygians. This was not well understood before, but Catherine and co-workers used fascinating evo-devo methods, catscan, recent lungfishes and salamanders, and fossils of early tetrapods to demonstrate this. Perhaps even more interesting, the front and hind limbs of tetrapods are remarkably similar, despite that the pelvic girdle of actinopterygians is a very tiny little plate of bone compared to the complex pectoral fin base. Catherine has advanced a theory about how the pelvic girdle developed into a support for the hind limb in tetrapods (making them four-legged). The real mystery, however, for me at least, is how come the hind foot is so similar to the front foot, and in particular, how come they both have five digits? Is this really the magic number? A handy come in pleiotropy?

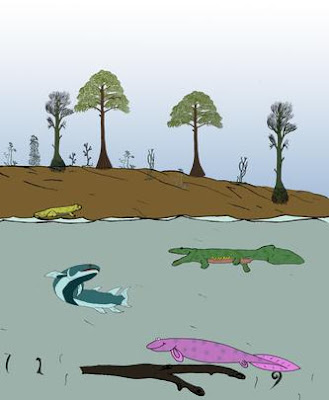

Most fish that walk about use only one pair of limbs, either the pectoral fins, or, rarely (as in skates) the pelvic fins. It seems likely that early tetrapods were more like mudskippers than skates, but who knows.

My big question, which I never got to ask Catherine, is: what forced the fish up on land? I know the answer is out there somewhere, but I am always surprised at my prejudicial assumption that fish evolved into tetrapods. Or tetrapods evolved from fish. (Or aquatic animals have an intrinsic evolutionary tendency to become terrestrial). An obvious explanation would be that water was first, land later, and seemingly all fish ancestors were aquatic. It is still possible for a protist to have become terrestrial and evolved into a tetrapod without actinopterygian intervention (or they became insects?). So, the conclusion must be that those early fish that took on fingers were right away driven out of the water. Today’s terrestrial fishes, and our close relatives the lungfish, live in shallow water, swamps, and mangroves, in very particular habitats with strong seasonal or diel changes in water level. Maybe the mudskipper will take over the planet after us. It looks sympathetic anyway. Still has to do something about its hind limbs.

Image by Catherive Boisvert: Devonian landscape and fish actors making evolution.