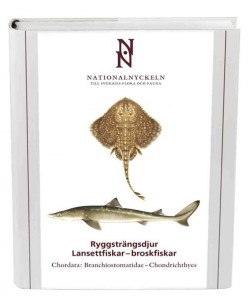

Today is the offcial release day of the 13th volume of the The Encyclopedia of the Swedish Flora and Fauna, dedicated to lower chordates, ie., lancelets, tunicates, hagfish, lampreys and chondrichthyans. It also comes with an introduction to chordates and to craniates, the latter sprawling with colorful dino drawings. Although I am first author, most of this tome is about tunicates with fantastic images from within and without that makes it a particulatly worthwhile reading (and buying, come on it is only SEK 345 and you get the sharks for free!) Thus, tunicate expert Thomas Stach, Freie Universität Berlin, and the late Hans G. Hansson, Tjärnö Marine Biological Laboratory, provided most of the species in this volume. But it also has one hagfish, three lampreys, and 29 chondrichthyans.

Today is the offcial release day of the 13th volume of the The Encyclopedia of the Swedish Flora and Fauna, dedicated to lower chordates, ie., lancelets, tunicates, hagfish, lampreys and chondrichthyans. It also comes with an introduction to chordates and to craniates, the latter sprawling with colorful dino drawings. Although I am first author, most of this tome is about tunicates with fantastic images from within and without that makes it a particulatly worthwhile reading (and buying, come on it is only SEK 345 and you get the sharks for free!) Thus, tunicate expert Thomas Stach, Freie Universität Berlin, and the late Hans G. Hansson, Tjärnö Marine Biological Laboratory, provided most of the species in this volume. But it also has one hagfish, three lampreys, and 29 chondrichthyans.

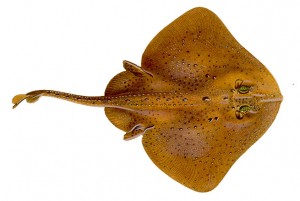

What you will like most about this volume is probably the graphics. For the craniates major contributing artists Linda Nyman and Karl Jilg, guided in the intricate details by Bo Delling, have excelled in creating live-to-touch impressions of fish and the like that few of us have actually seen alive and healthy.

Given that there already many shark books, not least the excellent compilations by Leonard Compagno, and volumes dedicated to hagfish and lampreys, and of course there is FishBase, one might as author feel like facing a table already laid with easily digested goodies. Especially in a species-poor country like Sweden with an ocean part that on a world map looks like you can jump over it to land dry. This is not so. Thousands of fisheries and fish biology papers appear every year, and still nobody seems to know what marine fish eat, how big they get, how they reproduce, how old they get, or even where they occur or what they look like. Nobody even knows which one is one of the biggest skates in Europe, Dipturus batis. Honestly, von Bertalanffy curves carry no meaningful biological information.

Nevertheless, it was indeed possible to provide details on all the Swedish species of hagfish, lampreys and chondrichthyans. It took six years to complete this volume, but rewardingly for all involved it feels like one has now turned pages entering into a new era of fish information in Sweden with the first real updated national fauna since 1895 in Skandinaviens fiskar (Fries et al., 1836-1857; Smitt, 1892-1895), and a worthy replacement to the popular standard Våra fiskar (Curry-Lindahl, 1985). It summarizes current knowledge and it provides a new platform for ecological and taxonomic research. And yes, of course the ray-finned fishes were not forgotten. They have been worked out in parallel and will be published in a separate fish-only volume to appear in the autumn of 2012.

The Encyclopedia is a project started at the Swedish Species Information Centre in Uppsala in 2001 and aims to produce a series of identification handbooks with keys in Swedish and English to the Swedish plant, fungi and animal species. It is a long-term project, aimed at covering the 30 000-40 000 species which can be identified without highly advanced equipment. They will be described in detail, including information on distribution and biology. For most of them, distribution maps as well as illustrations will also be provided.

With the present volume, there is now a newly published checklist of Swedish lancelets, cyclostomes and chondrichthyans. It is not long, so here it comes before it gets outdated. Species known only from occasional records are annotated. For those interested in Nordic exotisms, you also get the Swedish name.

Branchiostoma lanceolatum (Pallas, 1774) lansettfisk

Myxine glutinosa Linnaeus, 1758 pirål

Petromyzon marinus Linnaeus, 1758 havsnejonöga

Lampetra fluviatilis (Linnaeus, 1758) flodnejonöga

Lampetra planeri (Bloch, 1784) bäcknejonöga

Chimaera monstrosa Linnaeus, 1758 havsmus

Lamna nasus (Bonnaterre, 1888) håbrand

Cetorhinus maximus (Gunnerus, 1765) brugd

Alopias vulpinus (Bonnaterre, 1888) rävhaj

Galeorhinus galeus (Linnaeus, 1758) gråhaj

Mustelus asterias Cloquet, 1821 nordlig hundhaj

Carcharhinus longimanus (Poey, 1861) årfenhaj (single record)

Prionace glauca (Linnaeus, 1758) blåhaj

Galeus melastomus Rafinesque, 1810 hågäl

Scyliorhinus canicula (Linnaeus, 1758) småfläckig rödhaj

Scyliorhinus stellaris (Linnaeus, 1758) storfläckig rödhaj (two records)

Hexanchus griseus (Bonnaterre, 1788) sexbågig kamtandhaj (single record)

Somniosus microcephalus (Schneider, 1801) håkäring

Etmopterus spinax (Linnaeus, 1758) blåkäxa

Squalus acanthias Linnaeus, 1758 pigghaj

Oxynotus centrina (Linnaeus, 1758) trekantshaj (single record, actually from Danish Skagerrak)

Squatina squatina (Linnaeus, 1758) havsängel (single record)

Torpedo nobiliana Bonaparte, 1835 darrocka (two records)

Dipturus batis (Linnaeus, 1758) slätrocka (apparently two species involved)

Dipturus linteus (Fries, 1838) vitrocka

Dipturus nidarosiensis (Storm, 1881) svartbuksrocka (single record)

Dipturus oxyrinchus (Linnaeus, 1758) plogjärnsrocka

Leucoraja fullonica (Linnaeus, 1758) näbbrocka (two records)

Amblyraja radiata (Donovan, 1808) klorocka

Raja clavata Linnaeus, 1758 knaggrocka

Rajella fyllae (Lütken, 1887) rundrocka (single record)

Dasyatis pastinaca (Linnaeus, 1758) spjutrocka

Myliobatis aquila (Linnaeus, 1758) (single record)

References

Curry-Lindahl, K. 1985. Våra fiskar. Havs- och sötvattensfiskar i Norden och övriga Europa. P.A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag, Stockholm

Fries, B. Fr., C. U. Ekström & C. J. Sundewall. 1836 -1857. Skandinaviens Fiskar. P. A. Norstedt & Söner, Stockholm, IV+222 pp. Appendices 1-44, 1-140, pls. 1-60. Fascicle 2-3 (1837), 4 (1840) 5, 1839 (p. 111 dated 22 October 1839, ) 6+pls 31-36, Latin text 57-72 (1840), 7+pls 37-42, Latin text 73-92 (1842)

Kullander, S.O., T. Stach, H.G. Hansson, B. Delling, H. Blom. 2011. Nationalnyckeln till Sveriges flora och fauna. Ryggsträngsdjur: lansettfiskar-broskfiskar. Chodrata: Branchiostomatidae-Chondrichthyes. ArtDatabanken, Uppsala. 327 pp.

Smitt, F.A. 1892. Skandinaviens fiskar målade af W. von Wright beskrifna av B. Fries, C.U. Ekström och C. Sundevall. Andra upplagan. Bearbetning och fortsättning. Text. Förra delen. P.A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag, Stockholm, pp. 1-566+I-VIII+2 pp.

Smitt, F.A. 1895. Skandinaviens fiskar målade af W. von Wright beskrifna av B. Fries, C.U. Ekström och C. Sundevall. Andra upplagan. Bearbetning och fortsättning.Text. Senare delen.. P.A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag, Stockholm, pp 567-1239+1 p.

Smitt, F.A. 1895. Skandinaviens fiskar målade af W. von Wright beskrifna av B. Fries, C.U. Ekström och C. Sundevall. Andra upplagan. Bearbetning och fortsättning. Taflor. P.A. Norstedt & Söners Förlag, Stockholm, pls I-LIII, pp. I-III.