Has it not happened that you use Google search to search for images of say Danio rerio (a well-known fish). You get 16 900 hits. Unfortunately it is all too impossible to find a fish on many of those photos, because Google finds pages with the text Danio rerio having an image. And it takes time to browse through 16 900 images. This kind of image search is useful for finding the unexpected, such as anatomical drawings, phylogenetic trees, and people working on zebrafish, and definitely worth trying now and then. Without the image filter, you get 1 510 000 hits for Danio rerio, and that is just too much to browse in the hope of finding an image of the fish.

Google Labs now have a new tool under development that looks promising. It is called Similar Images, and uses some kind of image pattern recognition. What you do hear is that you specify a search for images as usual, e.g., Danio rerio, get the same result (but 16 500), but some images have the link “similar images”. Click one of those, and you get a subset of the 16 500, and on succeeding searches using the same method, you get down to 300-500 look-alike images, and most likely you have exactly what you want within reach.

This might be a tool for matching photos of unidentified fish specimens, and could also be helpful to check fish identifications on the web. Maybe could be used for other things than fish? Seems to work well with Paris Hilton (a well-known human), but for what …?

Danio rerio from Wikipedia © Free use

Fish do not have fingers?

Although actinopterygian radiation seems to have made the most significant footprint in vertebrate diversity, with more than 30 000 Recent species, there are also scientists who looking into the origin of the less successful group, the sarcopterygians, among which the tetrapods are the terrestrial ones – except that some escaped back to the water (sirenians, seals, cetaceans, and the like).

Attending Catherine Boisvert’s defence of her dissertation The origin of tetrapod limbs and girdles: fossil and developmental evidence recently, I came to realize that the evolutionary quirk with tetrapods is not the possession of limbs – lots of actinopterygians have limbs, and many tetrapods lack them – but the presence of fingers. Catherine’s thesis is about the evolution of fingers and the pelvic girdle. The digits (fingers) sit at the end of the autopod (the hand and foot of tetrapods) and are homologous with the distal radials of the dermatotrichs (fin-rays) attached to fish proximal radials (the pectoral-fin base, homologous with the sarcopterygian/tetrapod limbs). Interestingly, the finrays and the digits form before the autopod and proximal radials in both sarcopterygians and actinopterygians. This was not well understood before, but Catherine and co-workers used fascinating evo-devo methods, catscan, recent lungfishes and salamanders, and fossils of early tetrapods to demonstrate this. Perhaps even more interesting, the front and hind limbs of tetrapods are remarkably similar, despite that the pelvic girdle of actinopterygians is a very tiny little plate of bone compared to the complex pectoral fin base. Catherine has advanced a theory about how the pelvic girdle developed into a support for the hind limb in tetrapods (making them four-legged). The real mystery, however, for me at least, is how come the hind foot is so similar to the front foot, and in particular, how come they both have five digits? Is this really the magic number? A handy come in pleiotropy?

Most fish that walk about use only one pair of limbs, either the pectoral fins, or, rarely (as in skates) the pelvic fins. It seems likely that early tetrapods were more like mudskippers than skates, but who knows.

My big question, which I never got to ask Catherine, is: what forced the fish up on land? I know the answer is out there somewhere, but I am always surprised at my prejudicial assumption that fish evolved into tetrapods. Or tetrapods evolved from fish. (Or aquatic animals have an intrinsic evolutionary tendency to become terrestrial). An obvious explanation would be that water was first, land later, and seemingly all fish ancestors were aquatic. It is still possible for a protist to have become terrestrial and evolved into a tetrapod without actinopterygian intervention (or they became insects?). So, the conclusion must be that those early fish that took on fingers were right away driven out of the water. Today’s terrestrial fishes, and our close relatives the lungfish, live in shallow water, swamps, and mangroves, in very particular habitats with strong seasonal or diel changes in water level. Maybe the mudskipper will take over the planet after us. It looks sympathetic anyway. Still has to do something about its hind limbs.

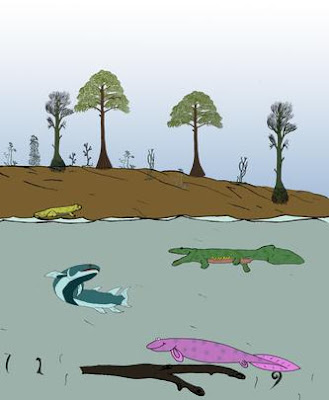

Image by Catherive Boisvert: Devonian landscape and fish actors making evolution.

Vandals in Nomenclature?

The discussion recently in the iczn-list (yes, an e-mail discussion about matters related to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) has been heated by vandals. That is, strong feelings have been expressed about vandals in taxonomy.

The reason there are vandals is because there is a definite ethically correct behaviour in matters nomenclature, and because Zoological Nomenclature is one of the oldest and best functioning globally endorsed anarchistic systems in history. There are rules, but it is up to the users of names to follow the rules. Strangely, it works most of the time. Vandals are those that do not follow the community rules, but abuse the system, taking advantages they should not have. Abusing freedom is inviting control. And that may not in the end make the world better.

Taxonomic vandals are of a few different kinds (my classification).

(1) Hooligans. These folks are absolute nuts about publishing new names. Whether their species exist or not is irrelevant to them. In the most recent example discussed, author A published a description of species B, and then copy pasted the same description for species C. This seems to be a pest among herpetologists and malacologists.

(2) Nominomaniacs. Nominomania is the obsession with scientific names, which in itself is possibly harmless, but there are bad guys (men only) here. Nominomaniacs of the bad kind eat homonyms like caterpillars chew leaves. They make new names for every junior homonym they can find, without checking up the organism, or whether a specialist may not already be concerned with these homonyms. Nominomaniacs are frequently authors of names outside their group of speciality, if they have any.

(3) Mihi-itchers. These people cannot leave any variation in nature without a name. Somehow they also frequently happen to publish a first name for the same species as a colleague is working on. A special case of advanced mihi itch is the Phylocode where you have to put a new name on every clade you may happen to find (I am provocative here). Mihi-itchers, like sneakers, lurk among the posters at conferences, take photos, and save many days of work efficiently and conveniently.

(4) Sneakers. Whenever a specialist has established a descriptive standard for a group, sneakers will copy paste his/her descriptions, make a few changes and apply it on their own species, preferably ones that are already under study by a specialist. Aquarium hobbyists do this, because they have no training in ichthyology and do not know what they are looking at. Students may be tempted to take this easy road as well.

They are not many, maybe 10 or so in the world at any given time, but they upset people considerably. You know these persons because they as a rule do not participate in scientific meetings, usually run their own journal or exploit weaknesses in journals that do not have a strong editorial control, have no research funding, always have specimens from places where nobody else gets a permit to collect, etc.

Why is it so? Taxonomy has no impact factor of interest to society or funding, so why bother?. Psychological factors aside, Nomenclature has one major problem called authorship. It is more or less obligatory to put the name of the person(s) who described a species after its scientific name.

Consider Dicrossus filamentosus (Ladiges, 1958).

Ladiges did a not very good one on this species; it was published as a sort of preliminary description in an aquarium magazine, based on two very dead aquarium specimens without locality, described by a non-specialist. It is a distinctive species, so no real harm done, and there were no specialists on South American cichlids available at the time. Most of the relevant information about the species, including geographical provenance only appeared with my redescription in 1978 (a student paper, not so advanced, but still helpful). Ladiges will forever be cited as the author of the species, although he did not do anything useful with it. Later workers will be more helped by Kullander (1978), which is practically never cited.

I take this particular example to show that even if the scientific basis for a description is very, very weak, it frequently gives more citation and more food for the ego than any other work on that species later. Confounding authorship associated with scientific names with scientific citation is bad in itself, but it also certainly is a major driving force in taxonomic vandalism.

In science elsewhere, bad or boring (like taxonomic papers) papers never get cited again, and their authors are peacefully brought to oblivion. The only way outside taxonomy to obtain a reputation is to work hard to do something useful.

The end result is that we have an extra number of useless names that specialists must consider for the rest of their professional career; we have lots of duplicate work, blocked access to relevant specimens, type specimens deposited in private collections unavailable to specialists, loss of trust in the profession, and in the end uneasiness and unwillingness among professionals to communicate openly about their work.

The Code of Ethics in the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, is very straightforward about what behaviour is expected from those making nomenclatural statements. In the case of my lab, we work on the systematics of danionine cyprinid fishes, the genus Puntius, South American cichlids, and in collaboration the fishes of Myanmar and Paraguay. I am not expected to check with others whenever I have a new species in these groups, and there are many of them. Everyone knows that we work on these fishes (or would have known if the Newsletter had existed; see previous blog). You do not have to check with me if you are thinking of describing a new species of goby from the Seychelles. But if I would find a new goby from the Seychelles I would need to check if somebody else might be working on it. And anyone working on any of the above groups is expected to check with me first, and with other colleagues that have known interests in the same area.

Two weeks ago I received a new species of fish; concluding it was new and interesting enough to describe, I checked with another specialist on that family two days ago, and it turned out he has the same species from the same place, so we have to make an informed and friendly decision how to go about it.

The job of the taxonomist is to a large extent to give scientific names to organisms. It is a little reward on top to the sometimes repetitive analytical work. Of course, we all get a little of the mihi itch (mihi means mine; this itch is about appending one’s name to species names), but it easily cured. However, among the many, many scientists in Ichthyology that I respect, all of them were always more concerned with the analysis than with their author status, and more concerned with having a publication that people want to read and use, than having their names cited. That is what science is about.

So, what should we do? Outlaw some people or journals? Permit only certain journals to publish nomenclatural acts? Apply to the Commission for suppression of every name not considered appropriate for whatever reason? Ignore the names published by vandals?

In the end, who judges vandalism? When am I a 100% vandal, or a 10% vandal or perfectly non-vandal, in the eyes of 5%, 50% or 100% of my colleagues? Is this about people or about the Code? Who is more mihi-itchy at the end of the day, the vandal or the vandalised? Ethics cannot be ruled, it can only be demonstrated. So, I would prefer to leave the system open, with the very slight disadvantages it may have. But the Code of Ethics of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature maybe should be more widely known.

What does the Zoological Code say then. I quote the most relevant parts of the Code of Ethics from the ICZN website:

1. Authors proposing new names should observe the following principles …

2. A zoologist should not publish a new name if he or she has reason to believe that another person has already recognized the same taxon and intends to establish a name for it (or that the taxon is to be named in a posthumous work). A zoologist in such a position should communicate with the other person (or their representatives) and only feel free to establish a new name if that person has failed to do so in a reasonable period (not less than a year).

3. A zoologist should not publish a new replacement name (a nomen novum) or other substitute name for a junior homonym when the author of the latter is alive; that author should be informed of the homonymy and be allowed a reasonable time (at least a year) in which to establish a substitute name.

4. No author should propose a name that, to his or her knowledge or reasonable belief, would be likely to give offence on any grounds.

5. Intemperate language should not be used in any discussion or writing which involves zoological nomenclature, and all debates should be conducted in a courteous and friendly manner.

6. Editors and others responsible for the publication of zoological papers should avoid publishing any material which appears to them to contain a breach of the above principles.

Some interesting examples where opinions are strong:

Adamas Huber 1979 replaced by Fenerbahce Özdikmen et al. 2006

What herpetologists talk about

Where are the ichthyologists?

I have admired some MySpace pages by non-ichthyologist colleagues, complete with all personal data, list of publications, etc. They remain there even after said colleagues have moved from the address they left there. Maybe MySpace is not their or my kind of space.

I tried LinkedIn, which is a community for mostly business people, but does not offer much of services. There is a lot of people there that I know, but not much I can do except have the contact details up, and wait for a chain of contacts to grow. It says that I am linked to 33 900 other professionals. I do not know if that is good or scary, but it is more people than I know personally.

FaceBook is fun, and promises plenty. It seems to be a place where a few wrong clicks can open you up to the whole world to come say hello to you. That is not really my idea, as I am quite non-social in a way. FaceBook is not a professional meeting point.

Wait a minute, there was a community for systematic ichthyologists! It was the Newsletter of Systematic Ichthyology, which was published as xerox copies by Bill Eschmeyer and ichthyology staff at the California Academy of Sciences, largely handmade I understand. You had to send in a formatted resumé of what you “are doing now” (before Twitter …) and CAS colleagues formatted and sent it out. It was very helpful and spared you time and money otherwise to waste on going conferences. Helpful because you learned about what people were doing so you could avoid doing the same, or contact them if there seemed to be some interesting information around.

The Newsletter then was acquired by a project called DeepFin, which was about collaborative molecular fish phylogenies. And with that the collaborative newsletter disappeared in some cybervacuum.

And yesterday, I found the solution, which this time was not an ichthyological invention, but seems to be the platform we could make use of. It is called Epernicus, and apparently was developed at Harvard University, just as a social and professional community. What differs is that it is tailored for scientists, providing for each person a sort of presentational web page with space for academic exams, list of publications and CVs. For me that helps a lot, because I have a safe space for my publication list on the web, and I do not need to carry it with me all the time, and others can quickly find it and contact me for a reprint (I have a lot of publications in the grey literature sphere). There are many occasions in life when a CV and publication list is requested, and only a few of these times are convenient in terms of searching for them.

Why not set up a personal web page somewhere and it will always be found by a search engine? Yes, sure, would be nice, but I am tired of web-authoring. Also, with the available online tools provided by Google (like this blog), Twitter, Facebook, Epernicus, etc., I am not bound to any particular computer. For some of these web resources I can use my mobile phone to update the web information. Well, with this blog, Epernicus CV, Twitter so my family can keep track of me, gmail, and the Google office suite, I feel I have moved away one more bit from the desktop computer prison, and into something more difficult to figure out how it works, and certainly at the heart of the grid. But this is only the beginning of how the web will become a much less physical resource over the next few years. If there are any ichthyologists out there, let’s meet at Epernicus. Maybe someone can inform me what the word epernicus means?

And, yes, I have read The Traveller and The Dark River. Find out what’s up in the Vast Machine.

From fishes to ZooBank

Fishes are among the most informatized organisms that I know. There may be a number of reasons for that, but reasons aside, the fact is that Daniel Pauly and Rainer Froese created FishBase independently of Bill Eschmeyer’s Catalog of Fishes, and ichthyologist Julian Humphries created the museum collection database with the collection management system MUSE back in the late 1980s, giving fish collections a head start in informatics. Since 1976 Joseph Nelson has published the Fishes of the World, now in its fourth edition, as an index to systematic ichthyology and with an eclectic classification.

Whereas FishBase has a given hit rate of 20 million per month and so is doing fine, the Catalog of Fishes is maybe less well known. It started first as a catalog of genera of fishes, but was expanded and eventually published as three huge volumes with scientific names of fishes, over 50 000, complete with type locality, current status, and literature reference. It is presently a web resource and updated frequently. For the layman it may look like just too boring, but for the scientists it is a goldmine saving enormously on the time of finding information about specific species and their names.

This kind of compilations is important, because biodiversity research is facing now an enormous problem with names. There may be 1.8 million named species, and many more million out there to be found, but only a million or so species have been secured in databases. And every year at least 16 000 new species are described.

GBIF have an initiative called the GNI (Global Names Index) to harvest all names, and a structure, the GNA (Global Names Architecture) to manage them. They will do this together with other acronyms such as PESI. In the meantime, the Catalogue of Life, a collaboration including the US ITIS and global consortium Species2000, have a checklist of the world’s species with just a little over 1 million in, and where FishBase is one of the best parts.

But we cannot have it like this, endlessly chasing names that people drop here and there in more or less obtainable publications. Zoological and Botanical nomenclature have to go modern and collaborate with information society. There have to be a registration system for names, and the habit of paper publication has to go away in favor of digital publication.

To those not familiar with nomenclature, the situation is the following: For a name to be available and thus accepted to use as a scientific name for a species, genus, or family, it has to be published on paper with a few more simple conditions such as a certain number of copies and a degree of obtainability. It is perfectly OK to publish 2 copies of a species description and give them away to 25 people who all except one throw their copy away within 24 hours. The single surviving copy is now the globally accepted token for the name of that species. Not surprising that many taxonomist spend most of their time searching for publications instead of doing real research.

Digital-only publishing is not permitted. Well, there is an exception for CD-ROMs with deposition in libraries, but it is a bit awkward and it may be difficult to find those CD-ROMs.

The International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature is the body that writes the rules for Zoological Nomenclature – of course with the needs and well-being of the taxonomic community taken good care of. The Commission is now seriously considering digital-only, what we call e-only publishing of zoological names; and seriously considering a registration system for old and new names.

Both proposals are controversial. Concerning e-only publising there is now a proposed amendment to the Code, and the Commission has invited comments and discussions. Some of the discussion is now published, and worth reading.

Formalisation of ZooBank as a registry for new names is maybe a bit further away, but unavoidable. In contrast to a Code amendment, it requires an infrastructure and running funds that are not immediately available. Nevertheless, Richard Pyle, ichthyologist at the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Hawai’i, is working day and night to build up the structure for ZooBank. You can already get a glimpse of the future from the development site. There are already much more than 5 000 nomenclatural acts registered.

ZooBank will have a healthy starter boost from Catalog of Fishes, so from a fish perspective this is perhaps no big step forward. But notice, there is an ichthyologist programming ZooBank!

Yes, Ichthyology rules biodiversity informatics …

Sturgeon fever

A sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus) once owned by King Adolf Fredrik, studied by Linnaeus,

now housed in the Swedish Museum of Natural History collections.Photo A. Silfvergrip. Data . Image CC-BY.

Once upon a time there was in the Baltic Sea a fish known as the sturgeon. Its existence in Swedish waters were known to Linnaeus and Artedi, and Linnaeus named it Acipenser sturio in 1758, based on two small specimens in alcohol, and a skin, plus literature records. These two alcohol specimens are still in the collection of the Swedish Museum of Natural History. One comes from Amsterdam apothecary Albertus Seba, bought by King Adolf Fredrik probably 1752, the origin of the other one is more obscure.

From 1758 till recently the sturgeon was studied, fished, eaten and extinguished from European waters, save for a declining population in the French river Garonne, which defies rapid extinction despite cadmium poisoning and sexually asynchronous breeding (males and females do not breed at the same time …). Then a German-US team in 2002 (Arne Ludwig et al.) could show that the northern European and Baltic Sturgeon is genetically the same as the North American Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus Mitchill, 1815, and not at all the same as the sturgeon in France, the Mediterranean, and the Black Sea.

Ooops … And this had already been demonstrated by morphological studies, that somehow did not draw the right conclusions.

Whereas there are still technical issues over which name goes to which species, the preliminary conclusion is that in the Garonne swims Acipenser sturio, and in the North Sea and the Baltic Acipenser oxyrhinchus was as much at home as in the United States.

The Baltic sturgeon is extinct in Europe. The last specimen identified as A. sturio in the Baltic died in 1996, and was an A. oxyrinchus.

Nevertheless, Swedish media the last two days have enthusiastically declared the return of the sturgeon! Based on a fish taken outside the island of Öland in the Baltic Sea, 10 of April by fisherman Ulf Åkerlund.

From the local newspaper scoop we learn that the fisherman is excited (as he should be; this is an uncommon fish whatever it is), and the Fisheries Board expert is more interested in tasting the roe than getting it properly identified.

From the published image, you can see the mutilated pectoral fin indicating a pond cultured fish. And what more, it looks not like a sturgeon but resembles more the Russian sturgeon Acipenser gueldenstaedti, and could also represent Siberian sturgeon Acipenser baeri. Although there are efforts to reintroduce Acipenser oxyrhinchus into the Baltic, I am not informed of any releases having taking place yet. If and when it happens it will be a great waste of money on a lost case.

The “sturgeons” we now have in the Baltic are escapes from cultures of Siberian and Russian sturgeon and hybrids between different species. They look like sturgeon because all 20+ species of sturgeons look about the same. In May 2000 a small “sturgeon” was caught in Kalmarsund strait and given to the Swedish Museum of Natural History (NRM). The specimen was sequenced and blasted as Acipenser stellatus, which it is not, and morphologically identified as A. baeri.

Other more or less recent Swedish “sturgeons” include a Siberian sturgeon from the Stockholm Archipelago in 1969, a Russian sturgeon from Lysekil in 1970, and one “sturgeon” from Skåne in 2007 that, like one from Kummelbank in 1991, has not been identified yet. Browse sturgeon data in the NRM fish collection.

Will we know which species was caught this time? It would be a good thing to build up knowledge as early as possible about potential “sturgeon” invasions in the near future, and we could learn more how to identify the fishes, and using molecular and morphological markers track the movements of these aliens in our waters. Let’s see what tomorrow has in store.

Fish from nowhere

Yesterday I mentioned briefly the leopard danio, a small golden fish full of dark spots, apparently a color mutation in the zebrafish Danio rerio, but described in 1963 as a species on its own with the name Brachydanio frankei. The leopard danio is a popular aquarium fish in its own right, which keeps its colors but does not differ in behaviour or size from the zebrafish, and hybridises freely with zebrafish. When it first appeared in the aquarium trade, its origin in the wild was unknown. That should have called for some caution … On the other hand, who could believe other than that the differences in colour pattern was a strong indicator of species distinctness?

Spotted danios are known from the wild, however. There is Danio kyathit from northern Myanmar, in which the spots are more or less irregularly arranged in rows, and many morphological characters distinguish it from other species of Danio. Described by Fang in 1998, based on four specimens she collected herself, she also included two specimens collected in the 1920s that were not spotted but striped. There was simply no way of distinguishing the striped and spotted kyathit other than by colour pattern, and because the rows of spots are merely broken up horizontal stripes, there was room for considering intraspecific variation. How different conclusions can be once you know a little more about the group you are working with!

Here is an image of Danio kyathit, photographed by Fang Fang.

The other spotted danio has no scientific name yet. It is a small fish, similar to Danio rerio but with large spots on the side. It is already available in the aquarium trade where it is called Danio sp. Burma. Will anyone dare to describe it? Is there a striped counterpart already available among the many supposed synonyms of Danio rerio??

A real sunshine story is the that of the “Odessa barb”, one of the major aquarium fish species, and belonging to the large family of cyprinid fishes. Males are marked by a stunning, glowing, deep, exquisitely brilliant red band along the side, and contrasting black spots in the dorsal, anal, and pelvic fins. Females are less colourful. It is or relatively small size, less than 5 cm, and easy to reproduce in aquarium.

The early aquarium history of the “Odessa barb” is not well documented. In 1973, Russian aquarist Dazkewitsch wrote that it originated from a market, not stated where, and arrived in Odessa, Ukraine, in 1971, soon being cultivated in Moscow. So it was named “Odessa barb” although quite evidently a South Asian species. It was a confusing time, a time for much speculation among American and European aquarists, and no information from Ukraine. And how come a small aquarium fish, soon of world fame could first be found in Ukraine, at the time part of the Soviet Union and with no aquarium fish import? Maybe it was also a “form” of some kind, like the leopard danio? Strangely, nobody got the idea this time to describe the new fish as a new species!

So, things remained for 30 years till Frank Schäfer in 2001, working for the German wholesale aquarium fish importer Glaser reported having found the “Odessa barb” in an importation from Myanmar.

Wow! And I and my colleague Ralf Britz (yes, that’s him with the vampire fish), missed it totally on our collecting trip in Myanmar just a little before, in 1998, crossing the country from Yangon in the south north to the foothills of the Himalayas in Putao.

Well, there was still no precise locality. And Ralf then found the fish in 2003, near Mandalay. So, it exists in nature, we know where, and last year we got it described. We named it Puntius padamya. Padamya is the Burmese word for ruby. The ruby barb of aquarists, however, is Puntius nigrofasciatus from Sri Lanka. The description is available online as an Open Access resource from the Electronic Journal of Ichthyology.

The “Odessa barb” freshly collected in the wild, a bit pale in the photo tank. Photograph by Ritva Roesler, from Kullander & Britz (2008: Electronic Journal of Ichthyology, 4: 56-66):

And the stately preserved holotype of Puntius padamya:

The lessons, if any, are: Don’t name fish known only from the aquarium trade. Be patient. And, give nice names to nice fish.

Zebrafish in spirits

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) are probably the most important fish for understanding humans. They are small fish, 2-3 cm long and native to India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. Most conspicuous about them is the contrasted coloration with alternating blue and white horizontal stripes, even extending onto the caudal fin. That means they are horizontal where zebras are vertical. Otherwise there are no similarities 🙂

Zebrafish occur in many places in India, in the north in the Indus, Ganga, and Brahmaputra as well as in Kerala in the south, but appear uniform in color pattern and other morphology. They live in schools in different habitats, and are often collected in large numbers. As aquarium fish they are hardy, easy to breed, and prolific.

The distinctive colour pattern, which can be genetically altered, ease of keeping, and the fast generation time contribute to zebrafish status as a so-called model organism, which developmental biologists use to study the development and inheritance of various structures. Recently also, zebrafish researchers have been helped by improved understanding of the systematics of the group of fishes to which zebrafish belong, so that structures can be studied comparatively in closely related species.

Here is a dead zebrafish in alcohol from Assam, India. Not very colourful, but useful for taxonomic studies.

I just spent two days writing a description of a new species that I and my student Te Yu Liao collected last year (about this time) in Myanmar. There are many species of fishes closely related to the zebrafish. Thirteen species have been named in the genus Danio, and at least ten more species remain to be described. Most fascinating among the zebrafish relatives, is the leopard danio, which turned up in aquarium circles in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s and was described as a new species with the name Brachydanio frankei. This form, with small dark spots all over the body and fins, has never been found in the wild. It is probably a mutant of zebrafish, differing only in the irregular colour pattern. The genus, however, includes species that are spotted for real.

I will come back to fish species that only exist in the aquarium trade later. Let us round off the day with some zebrafish entertainment.

If you need just an overview of zebrafish, with the basic data, try Fishbase.

Wikipedia insists on being very technical about zebrafish

These developing zebrafish embryos are just irresistible:

The Wolfgang Driever Lab at the University of Freiburg has still images so you can track all the details at different stages. Click the image (from their website) to enter the zebrafish anatomy:

And then there is an enthusiasts’s website with images of various zebrafish-like species, Pete Cottle’s Danios and Devarios.

In the beginning …

This is a fast start blog to introduce myself (only a glimpse) and what possible kind of writings can be expected here.

As an ichthyologist, I will write mainly about fish. I manage two e-mail lists, my twitter, and blogs for two projects. Let’s see if there is more to say.

As a biodiversity informatician, I will try to connect fish with computers. I already post biodiversity informatics news on a Swedish language blog. Let’s see if there is more to say.

Naturally, I must first introduce you to those wonderful resources.

cichlid-l is the discussion list for professionals and others interested in cichlids. Cichlids are freshwater fishes found in Africa, South and Central America, Madagascar and parts of Asia. It is the second or third most speciose family of fishes (and vertebrates). This list is fairly old, started in January 1995.

eurofish-l is the discussion list for all other ichthyologists, but with an intended focus on Europe and particularly the activities of the European Ichthyological Society.

I will be back about the access to these lists, since they currently seem to have been locked up behind the firewall.

The FishBase Blog is the news blog in FishBase. FishBase contains information about all the world’s fishes, available for free on the web, e.g., on the Swedish FishBase server.

The Swedish Fishbase team also maintains its own news blog, in the Swedish language.

And finally, GBIF-Sweden serves news form the biodiversity informatics world in the form of a blog.

Ah, twitter, somewhat neglected: http://twitter.com/svenok